Psychosocial issues in colorectal cancer survivorship: the top ten questions patients may not be asking

Introduction

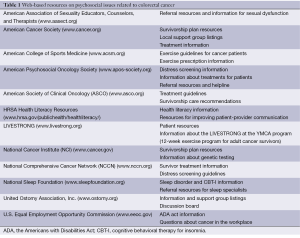

Advances in colorectal cancer screening and treatment have increased survivorship significantly in recent years, with the 5-year survival rates for all colorectal cancer patients estimated to be between 65-66% (1). Cancer survivors face a number of psychosocial challenges including sleep difficulties, pain, changes in sexual functioning, fear of cancer recurrence, financial hardship, and impaired quality of life (QOL) (2-4). While more and more resources are available for colorectal cancer patients to manage psychosocial issues related to survivorship, many patients may not feel comfortable initiating conversations with providers about these concerns. The following questions provide a summary of some of the most common patient concerns related to colorectal cancer survivorship and helpful resources that can help patients and providers manage these psychosocial issues (see Table 1 for full list of resources).

Full table

How long will my cancer-related distress last?

Survivors of cancer have a higher risk of developing anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (5,6). In colorectal cancer survivors, the prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms appears to be closely related to physical functioning, financial concerns, cognitive functioning, lack of social support, and concerns about cancer recurrence (7,8). Patients who are married or in long-term relationships and those who are physically active tend to report lower levels of anxiety and psychosocial distress (4,9). With these predictors and protective factors in mind, screening for survivors of colorectal cancer is recommended in order to identify patients who are experiencing clinically significant levels of distress, anxiety, or depression. Discussing these symptoms with physicians early in care also increases the likelihood that patients will report anxiety and depression if they occur later in treatment (10). This allows providers to make appropriate referrals for mental health treatment or additional support if needed.

In terms of screening methods, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has recommended that Distress Thermometers be implemented to assess level of distress and potential problems areas for patients. A cut-off score of 4 is generally recommended to identify patients who may be in need of further resources (11). Other questionnaires such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) can also be useful tools for anxiety and depression screening (11,12).

What will it be like going back to work?

Although approximately two-thirds of cancer patients return to work within 1.5 years after their diagnosis, unemployment rates are significantly higher in survivors of cancer (13). Returning to work after treatment may be beneficial for many colorectal cancer survivors as it can help patients to regain a sense of normalcy and routine, re-establish social support networks with co-workers, reduce financial distress, and increase activity levels during the day (7). However, some patients may have concerns about treatment effects on physical functioning and fatigue and whether or not they will be able to return to their previous jobs or continue to work full-time. Patients may also report a decline in cognitive functioning at their job including memory difficulties, concentration impairment, and decreased ability to multitask (13). Changes in bowel functioning, including constipation and diarrhea, are also associated with delays in returning to work for some patients (14).

A recent review of return-to-work interventions showed that multidisciplinary interventions involving physical, psychological, and vocational components have the highest return-to-work rates (15). Other studies have shown that receiving even brief advice or guidance from a health care provider may be very helpful to patients who are considering a return to work (16). Providers may be able to help patients more accurately assess their readiness to return to work, improve symptom management in the workplace, and provide guidelines for patients to monitor how they are adjusting to work (15,16). Patients may also benefit from information about legal protection through the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). For example, patients may not be aware of reasonable accommodations that their employers can consider as they return to work including restructuring jobs, offering modified work schedules, employee reassignment, or changes that can make the workplace more accessible.

What do genetic testing results mean for me and my family?

While approximately 75% of patients with colorectal cancer have no evidence of an inherited disorder, the remaining 25% of patients have a family history of colorectal cancer that suggests possible hereditary factors [National Cancer Institute (NCI) (17)]. The genetic mutations that have been identified as being linked to hereditary colorectal cancers only account for about 5-6% of colorectal cases currently, although it is likely that more genetic factors will be discovered in the future. For example, 2-4% of individuals diagnosed with colorectal cancer have Lynch syndrome, which predisposes them to colorectal cancer and other malignancies (18).

Studies estimate that 67% of colorectal cancer survivors are interested in screening for genetic factors (19). Patients considering genetic testing may have a number of questions related to how the results may affect their family members, whether or not insurance will cover the testing, and who may have access to their results in the future. Patients with higher levels of psychosocial distress, lower levels of perceived social support, and escape-avoidant coping styles may be less likely to request screening due to concerns about receiving genetic testing results (20). Referring patients to a genetic counselor to discuss testing options, costs, and implications of testing may help patients decide whether or not to pursue genetic testing as a colorectal cancer survivor. The NCI website also has patient materials available that can provide information about the legal, social and ethical concerns related to genetic testing.

Will my cultural background affect my QOL and care in the future?

Cultural factors including race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status are known to be important predictors of survivorship outcomes, with a disproportionate number of cancer-related deaths occurring among minorities (21,22). Patients in minority groups are more likely to report problems with the coordination of their treatment, access to care, and information about their treatment (21,23). Patients from diverse cultural backgrounds may be reluctant to participate in medical treatment that differ from their own beliefs and traditions, may experience fear and mistrust of healthcare institutions, or may have less experience or knowledge in terms of navigating the healthcare system. These differences can create barriers to patient care, misunderstandings between clinicians and patients, and poor adherence to recommendations for long-term treatment (22). Creating a more culturally sensitive treatment environment can involve an evaluation of patients’ beliefs and attitudes about cancer during treatment, involving the patient and family members in decision-making and treatment planning, addressing concerns related to health literacy and access to health care services, and providing patient materials in a culturally-tailored language/format (21).

How important is physical activity now that I have survived colorectal cancer?

Physical activity is an important for survivors of colorectal cancer, yet many patients may not feel comfortable engaging in exercise during or after treatment. Zhao and colleagues found that only 56.1% of cancer survivors reported engaging in physical activity at least 150 minutes per week vs. 65.7% of adults with no cancer history (4). This is partially due to inaccurate previous recommendations for cancer patients to avoid activity and to rest during treatment (24). Physical activity interventions in cancer survivors have been shown to have positive effects on upper and lower body strength, fatigue, QOL, anxiety, and self-esteem (25).

The American College of Sports Medicine has recommended that cancer survivors adhere to the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans which includes 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity and muscle strengthening activities at least 2 days per week (24). Although some patients will be able to increase their physical activity levels by following general exercise guidelines, most would benefit from more tailored recommendations that can take into account individual needs (26). This may include providing an exercise “prescription” that specifies type of activity, intensity, and duration. Referring patients to community-based exercise programs available at the YMCA may help to provide social support and guidance from trained professionals during their exercise program. If needed, a referral to physical therapy or rehabilitation may help patients to address weakness or instability that may be present due to the effects of treatment or deconditioning.

Will my primary care provider (PCP) be able to provide all of my care as a colorectal cancer survivor?

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends a model of care that combines the expertise of the oncology team and the PCP to coordinate survivor follow-up (27). However, patients and providers may have different expectations in terms of who will be providing their care after treatment ends (28). For example, some patients expect their oncology team to be more involved with their cancer care follow-up than their PCP. One of the ways to facilitate transfer of care back to the PCP is to create a survivorship plan that details all of the recommendations for the patient’s follow-up care and which providers will be responsible for each aspect of treatment. Giving both the patient and their PCP a copy of this survivorship plan helps to create the sense of a warm handoff with clear documentation of needs for additional treatment and monitoring (29). There are many resources available for creating survivorship treatment plans on the ASCO and American Cancer Society websites, including specific guidelines for colorectal cancer follow-up care.

What will it be like having my stoma long-term?

Colorectal cancer patients often have concerns about adjusting to their stoma including: changes in sexual behavior, clothing fit, proper fitting of the appliance, odor or noises related to use of a stoma, and changes in body image (30-32). Despite these concerns, research typically shows that QOL scores remain ‘good’ when patients are asked to rating living with a stoma (33). Referring patients to an ostomy nurse and providing resources from the United Ostomy Association of America can help to decrease patients concerns as they adjust to their stoma.

How will my sexual life be affected as a survivor?

Although sexual dysfunction is one of the most common long-term effects of colorectal cancer treatment, this issue is rarely discussed among patients and their providers (34). Changes in sexuality can include coital pain, erectile dysfunction, and/or decreased vaginal lubrication (35). Patients may be reluctant to initiate conversations about sexual functioning, so frequent assessment of these symptoms can help to normalize the discussion during follow-up visits. Regardless of age, sexual orientation, or partner status, sexual functioning is an important aspect of the QOL for all patients that should be monitored during survivorship care. In addition to providing patients with resources for sexual dysfunction treatment, a referral to a sex therapist or educator may also be helpful.

What if I continue to have problems sleeping after treatment ends?

It is not uncommon for people receiving treatment for a cancer diagnosis to have changes in sleep patterns including increase sleep onset latency and decreased total sleep (36). These disruptions in the sleep cycle may be associated with reduced tissue growth and repair, fatigue, impaired memory, and decreased QOL (37). When providers do not intervene, patients may self-medicate and potentially choose detrimental remedies, such as alcohol, to help them sleep (38). Although medications for sleep are often considered first-line treatment for insomnia, many patients could benefit from a behavioral approach to treatment which is associated with better long-term outcomes than pharmacological treatment. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is a multi-component treatment that is designed to improve sleep through sleep restriction and stimulus control techniques (39). CBT-I can be as effective as medication but without the side effects or potential for patients to rely on medications for sleep. In order to determine whether or not a patient may be a good candidate for CBT-I, providers should do a thorough assessment of their sleep difficulties to determine if a sleep study may be needed to rule out other sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

What will happen if my cancer comes back?

Fear of recurrence is common among cancer survivors (42-70%), and may not decrease over time even when risk of recurrence is low (40,41). It is also associated with poorer QOL, psychological comorbidities, and increased health care costs due to more frequent medical visits. Despite the negative outcomes associated with fear of cancer recurrence, it is not often discussed during follow-up appointments and patients may feel reluctant to ask questions about their risk of recurrence. Providing patients with a survivorship plan and giving them the NCCN recommendations for follow-up tests and appointments may reduce the uncertainty and apprehensions in the majority of survivors. For some patients, a referral to a behavioral health provider for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) may be helpful to reduce their fear of recurrence and associated symptoms (40,42). The American Psychosocial Oncology Society has more information and resources for patient referrals.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The views expressed in this abstract/manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the US Government.

References

- Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62:220-41. [PubMed]

- Faul LA, Shibata D, Townsend I, et al. Improving survivorship care for patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Control 2010;17:35-43. [PubMed]

- McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:631-40. [PubMed]

- Zhao G, Li C, Li J, et al. Physical activity, psychological distress, and receipt of mental healthcare services among cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2013;7:131-9. [PubMed]

- Boyes AW, Girgis A, Zucca AC, et al. Anxiety and depression among long-term survivors of cancer in Australia: results of a population-based survey. Med J Aust 2009;190:S94-8. [PubMed]

- Hoffman KE, McCarthy EP, Recklitis CJ, et al. Psychological distress in long-term survivors of adult-onset cancer: results from a national survey. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1274-81. [PubMed]

- Denlinger CS, Barsevick AM. The challenges of colorectal cancer survivorship. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2009;7:883-93. [PubMed]

- Gray NM, Hall SJ, Browne S, et al. Predictors of anxiety and depression in people with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:307-14. [PubMed]

- Chambers SK, Lynch BM, Aitken J, et al. Relationship over time between psychological distress and physical activity in colorectal cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1600-6. [PubMed]

- Mello S, Tan AS, Armstrong K, et al. Anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: the role of engagement with sources of emotional support information. Health Commun 2013;28:389-96. [PubMed]

- Patel D, Sharpe L, Thewes B, et al. Using the Distress Thermometer and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale to screen for psychosocial morbidity in patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer. J Affect Disord 2011;131:412-6. [PubMed]

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69-77. [PubMed]

- Groeneveld IF, de Boer AG, Frings-Dresen MH. Physical exercise and return to work: cancer survivors’ experiences. J Cancer Surviv 2013;7:237-46. [PubMed]

- Cooper AF, Hankins M, Rixon L, et al. Distinct work-related, clinical and psychological factors predict return to work following treatment in four different cancer types. Psychooncology 2013;22:659-67. [PubMed]

- de Boer AG, Bruinvels DJ, Tytgat KM, et al. Employment status and work-related problems of gastrointestinal cancer patients at diagnosis: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000190. [PubMed]

- Tamminga SJ, de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, et al. Return-to-work interventions integrated into cancer care: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med 2010;67:639-48. [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer genetics risk assessment and counseling. 2014. Available online: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/genetics/risk-assessment-and-counseling/HealthProfessional/page1

- Cragun D, Malo TL, Pal T, et al. Colorectal cancer survivors' interest in genetic testing for hereditary cancer: implications for universal tumor screening. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2012;16:493-9. [PubMed]

- Kinney AY, Choi YA, DeVellis B, et al. Attitudes toward genetic testing in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Pract 2000;8:178-86. [PubMed]

- Esplen MJ, Madlensky L, Aronson M, et al. Colorectal cancer survivors undergoing genetic testing for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer: motivational factors and psychosocial functioning. Clin Genet 2007;72:394-401. [PubMed]

- Guidry JJ, Torrence W, Herbelin S. Closing the divide: diverse populations and cancer survivorship. Cancer 2005;104:2577-83. [PubMed]

- Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin 2004;54:78-93. [PubMed]

- Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Guadagnoli E, et al. Patients’ perceptions of quality of care for colorectal cancer by race, ethnicity, and language. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6576-86. [PubMed]

- Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:1409-26. [PubMed]

- Speck RM, Courneya KS, Mâsse LC, et al. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv 2010;4:87-100. [PubMed]

- Stout NL. Exercise for the cancer survivor: all for one but not one for all. J Support Oncol 2012;10:178-9. [PubMed]

- McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:631-40. [PubMed]

- Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, et al. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2489-95. [PubMed]

- Virgo KS, Lerro CC, Klabunde CN, et al. Barriers to breast and colorectal cancer survivorship care: perceptions of primary care physicians and medical oncologists in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2322-36. [PubMed]

- Neuman HB, Patil S, Fuzesi S, et al. Impact of a temporary stoma on the quality of life of rectal cancer patients undergoing treatment. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:1397-403. [PubMed]

- Haanstra JF, de Vos Tot Nederveen Cappel WH, Gopie JP, et al. Quality of life after surgery for colon cancer in patients with Lynch syndrome: partial versus subtotal colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2012;55:653-9. [PubMed]

- Sun V, Grant M, McMullen CK, et al. Surviving colorectal cancer: long-term, persistent ostomy-specific concerns and adaptations. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013;40:61-72. [PubMed]

- Orsini RG, Thong MS, van de Poll-Franse LV, et al. Quality of life of older rectal cancer patients is not impaired by a permanent stoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013;39:164-70. [PubMed]

- Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, et al. The sexual health care needs after colorectal cancer: the view of patients, partners, and health care professionals. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:763-72. [PubMed]

- Den Oudsten BL, Traa MJ, Thong MS, et al. Higher prevalence of sexual dysfunction in colon and rectal cancer survivors compared with the normative population: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:3161-70. [PubMed]

- Berger AM, Grem JL, Visovsky C, et al. Fatigue and other variables during adjuvant chemotherapy for colon and rectal cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2010;37:E359-69. [PubMed]

- Wu HS, Davis JE, Natavio T. Fatigue and disrupted sleep-wake patterns in patients with cancer: a shared mechanism. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:E56-68. [PubMed]

- Gooneratne NS, Tavaria A, Patel N, et al. Perceived effectiveness of diverse sleep treatments in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:297-303. [PubMed]

- Garland SN, Johnson JA, Savard J, et al. Sleeping well with cancer: a systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in cancer patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014;10:1113-24. [PubMed]

- Butow PN, Bell ML, Smith AB, et al. Conquer fear: protocol of a randomised controlled trial of a psychological intervention to reduce fear of cancer recurrence. BMC Cancer 2013;13:201. [PubMed]

- McCollum KH, Wood FG, Auriemma K. Evaluation of a breast and colon cancer survivorship program. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2014;18:231-6. [PubMed]

- Taylor C, Richardson A, Cowley S. Surviving cancer treatment: an investigation of the experience of fear about, and monitoring for, recurrence in patients following treatment for colorectal cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2011;15:243-9. [PubMed]