Gastric metastasis of Merkel cell carcinoma, a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding: case report and review of the literature

Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon and a highly malignant cutaneous tumor of neuroendocrine origin, which frequently affects elderly Caucasian males. Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation and immunosuppression are important pre-disposing factors. Recently, Merkel cell polyomavirus has also been implicated in its pathogenesis (1). Histologically, MCC can appear similar to a variety of other small round blue cell tumors; hence, immunohistochemical studies play an important role in confirming its diagnosis. MCC has an aggressive biological behavior characterized by rapid growth, early distant metastasis and poor prognosis. The most common sites of metastasis of MCC include distant lymph nodes, distant skin, lungs, central nervous system and bone (2). Metastasis of MCC to the stomach is extremely uncommon and it is rarely described in the literature. In general, it is very uncommon for tumors to metastasize to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and small intestine is the most common site of tumor metastasis followed by stomach (3). We hereby describe a patient with gastric metastasis of MCC who presented with upper GI bleeding. Also presented is a review of literature to shed a light on clinical presentation, diagnosis and management of this rare tumor.

Case presentation

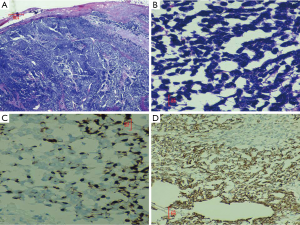

A 60-year-old Hispanic male presented to the emergency room with complaints of fatigue, weakness and passing maroon colored stools for five days. Originally, he had presented to our hospital 4 months ago with a right groin mass. This lesion was biopsied and a diagnosis of MCC was made after a battery of immunohistochemical tests (Figure 1A-D). Positron emission tomographic (PET) scan showed diffuse skeletal involvement and patient was started on chemotherapy (cisplatin and etoposide) and radiation therapy (RT).

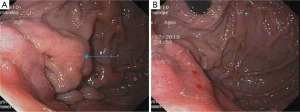

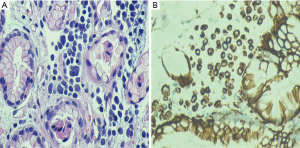

In his current visit, the patient denied any nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain. He denied having any history of peptic ulcer disease. He was taking aspirin and clopidogrel after stent placement for a recent event of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. On physical examination, he was normotensive but tachycardic with pulse rate of 130/minute. His abdominal examination was unremarkable with no tenderness, guarding or rigidity. Rectal examination showed maroon colored stools with blood clots. The rest of the physical examination was within normal limits. Laboratory studies showed pancytopenia due to ongoing chemotherapy with hemoglobin of 5.0 g/dL, platelets of 19 k/mm3 and white blood cell count of 1.4 K/mm3. His coagulation studies were within normal limits. Patient was resuscitated with intravenous fluids, proton pump inhibitor, packed red blood cells and platelet transfusions. Colonoscopy was unremarkable except for diverticulosis. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed malignant appearing gastric folds in the fundus and the body of the stomach (Figure 2A,B), which were biopsied; however no active bleeding was seen. Patient responded well to the conservative treatment measures and GI bleeding was thought to be due to low platelets, aspirin and clopidogrel. Biopsy results were consistent with the diagnosis of metastatic MCC to the stomach (Figure 3A,B). Chemotherapy had to be held after three cycles due to severe side effects.

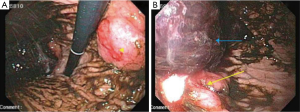

The patient returned one month later with similar complaints for which a repeat EGD was done. It showed a 3 cm, ulcerated mass near the lesser curvature of the stomach (Figure 4A) with a concurrent 4 cm ulcerated lesion in the gastric fundus with an adherent clot (Figure 4B). Active bleeding was seen after irrigation of the clot, which was controlled with local epinephrine injection and clipping. No further chemotherapy or RT was considered due to patient’s poor performance status.

Discussion

MCC is a rare and highly aggressive cutaneous cancer affecting elderly white males (1). It was first described by Toker in 1972 as Trabecular carcinoma (4). Subsequently, electron dense neurosecretory granules were demonstrated in the tumor cells and it was classified as tumor of neuroendocrine origin (5).

According to a population based study involving 3,870 cases of MCC, males were more frequently affected than females (61.5% vs. 38.5%). Moreover, a majority of cases were reported in whites between 60 and 85 years of age (94.9%), whereas blacks were rarely affected (6). Excessive exposure to the sun light is an important risk factor for development of MCC. It is more common in immunosuppressed individuals, such as those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, organ transplantation or lymphoproliferative malignancies (1). According to recent studies, Merkel cell polyomavirus has also been implicated to play an important role in the carcinogenesis of MCC (7,8).

MCC usually presents as a painless, firm, reddish or skin colored nodule on a chronically sun exposed area of the body (1). Highest incidence of MCC is seen in skin of the face (26.9%) followed by skin of the upper limb and shoulder (22.0%) and skin of the lower limb and hip (14.9%). MCC can also involve sun protected areas. Salivary glands, nasal cavity, lips, lymph nodes, vulva, vagina and esophagus were determined to be the most common extra cutaneous sites of involvement (6). Based on a study of 195 patients, Heath et al. has proposed a pneumonic “AEIOU”, to describe the most common clinical features of this tumor (A = Asymptomatic, E = Expanding rapidly, I = Immunosuppressed, O = older than 50 years and U = UV-exposed skin) (9).

However, MCC does not have any classic features of presentation and it is hardly ever thought of as a primary diagnosis. If it is suspected based on initial hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) of the lesion, further confirmation of the diagnosis should be performed by immunohistochemical staining. Microscopically, it presents as a small round blue cell tumor, differential diagnosis for which include metastatic small cell lung cancer (SCLC), small B-cell lymphoma and anaplastic small cell melanoma. Cytokeratin-20 (CK-20) is highly sensitive marker for MCC and it is positive in about 89-100% of cases, demonstrating a characteristic perinuclear dot-like staining pattern in tumor cells. Along with CK-20, MCC often stains positively with low molecular weight cytokeratin (CAM-5), neuron specific enolase (NSE) and synaptophysin. MCC stains negatively for thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) which helps in differentiating MCC from SCLC (1,10-12). MCC does not stain for S-100 or leucocyte common antigen (LCA), which are markers of melanoma and lymphoma, respectively (13,14).

MCC is an aggressive tumor and skin lesions grow rapidly over weeks to months. It is characterized by early local, regional and distant metastasis and frequent relapses. The incidence of local recurrence is 25-30%, regional disease is 52-59% and distant metastatic disease in 34-36% of all cases of MCC (15-17). The most common sites of distant metastasis of MCC are distant lymph nodes (27-60%), distant skin (9-30%), lung (10-23%), central nervous system (18.4%) and bone (15.2%) (2). MCC rarely metastasizes to the stomach and very few cases are reported in the literature. In a recent case study of patients with gastric metastasis of MCC by Syal et al., 78% of patients presented with upper GI bleeding and 67% of patients died within 4 months of diagnosis of gastric metastasis (18).

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) provide a detailed diagnostic and therapeutic approach for patients with MCC (19). In patients with asymptomatic primary MCC, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is the most sensitive method to diagnose nodal metastasis. Positron emission tomography-computerized tomography (PET-CT) scan is preferred when distant metastasis is suspected (19-21).

Surgery is the principal modality of treatment in patients with clinically localized MCC with or without RT. SLNB should be performed in patients with clinically N0 disease. In nodal positive cases without distant metastasis, regional lymph node dissection is performed with or without RT (19,22).

RT and chemotherapy are the mainstays of treatment in patients with advanced metastasis. Interdisciplinary approach and participation in clinical trial is recommended in cases of distant metastasis. Tumor stage and tumor size are the most important prognostic factors (19). Mortality rate of MCC exceeds that of malignant melanoma and the overall five years survival rate is between 30% to 64% (15-17,23).

In conclusion, MCC is a relentless, aggressive skin tumor. It lacks any classical clinical features and it is rarely suspected as a primary diagnosis. Immunohistochemical studies play an important role in the diagnosis. Gastric metastasis of MCC is exceedingly rare and carries dismal prognosis. Given the rarity of this tumor and lack of prospective clinical trials, no clear consensus exists about the best ways of management. Surgery is the primary modality of treatment in localized stages of cancer, whereas chemotherapy and RT are the mainstay of therapy in advanced cases. Interdisciplinary approach and participation in clinical trial is recommended in the management of this rare tumor.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Becker JC. Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2010;21 Suppl 7:vii81-5. [PubMed]

- Medina-Franco H, Urist MM, Fiveash J, et al. Multimodality treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: case series and literature review of 1024 cases. Ann Surg Oncol 2001;8:204-8. [PubMed]

- Samo S, Sherid M, Husein H, et al. Metastatic infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast to the colon: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2013;2013:603683.

- Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1972;105:107-10. [PubMed]

- Houben R, Schrama D, Becker JC. Molecular pathogenesis of Merkel cell carcinoma. Exp Dermatol 2009;18:193-8. [PubMed]

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol 2010;37:20-7. [PubMed]

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science 2008;319:1096-100. [PubMed]

- Kassem A, Schöpflin A, Diaz C, et al. Frequent detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinomas and identification of a unique deletion in the VP1 gene. Cancer Res 2008;68:5009-13. [PubMed]

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:375-81. [PubMed]

- Cheuk W, Kwan MY, Suster S, et al. Immunostaining for thyroid transcription factor 1 and cytokeratin 20 aids the distinction of small cell carcinoma from Merkel cell carcinoma, but not pulmonary from extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2001;125:228-31. [PubMed]

- Hanly AJ, Elgart GW, Jorda M, et al. Analysis of thyroid transcription factor-1 and cytokeratin 20 separates merkel cell carcinoma from small cell carcinoma of lung. J Cutan Pathol 2000;27:118-20. [PubMed]

- Scott MP, Helm KF. Cytokeratin 20: a marker for diagnosing Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol 1999;21:16-20. [PubMed]

- Czapiewski P, Biernat W. Merkel cell carcinoma - Recent advances in the biology, diagnostics and treatment. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2014. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Koljonen V, Haglund C, Tukiainen E, et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in primary Merkel cell carcinoma--possible prognostic significance. Anticancer Res 2005;25:853-8. [PubMed]

- Akhtar S, Oza KK, Wright J. Merkel cell carcinoma: report of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000;43:755-67. [PubMed]

- Gillenwater AM, Hessel AC, Morrison WH, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: effect of surgical excision and radiation on recurrence and survival. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001;127:149-54. [PubMed]

- Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2300-9. [PubMed]

- Syal NG, Dang S, Rose J, et al. Gastric metastasis of merkel cell cancer--uncommon complication of a rare neoplasm. J Ark Med Soc 2012;109:134-6. [PubMed]

- NCCN Guidelines version 1.2014. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Available online: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/mcc.pdf

- Schwartz JL, Griffith KA, Lowe L, et al. Features predicting sentinel lymph node positivity in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1036-41. [PubMed]

- Siva S, Byrne K, Seel M, et al. 18F-FDG PET provides high-impact and powerful prognostic stratification in the staging of Merkel cell carcinoma: a 15-year institutional experience. J Nucl Med 2013;54:1223-9. [PubMed]

- Tai P. A practical update of surgical management of merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. ISRN Surg 2013;2013:850797.

- Bichakjian CK, Lowe L, Lao CD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer 2007;110:1-12. [PubMed]